"There are four purposes of improvement: easier, better, faster, and cheaper. These four goals appear in the order of priority."

- Shigeo Shingo

The wisdom of this quote struck home recently, when I was writing my March newsletter on stretch goals. One problem with stretch goals, I believe, is that they focus on outcome metrics, and can therefore be gamed. The cost of a product or service is an incredibly important metric, but it, too, is an outcome metric, influenced by a huge variety of factors. Because of that, when a (non-lean) organization focuses on cost reduction, the most common first step is laying off people. The second most common step is downgrading the product specs, making the product both cheaper and "cheaper." Neither of these approaches are good for the worker or for the customer.

What's fascinating about this quote (to me, anyway) is that Shingo prioritizes worker health and safety above all else. First, the process must be made easier; then -- and only then -- should we worry about product quality, lead time, or cost. To be sure, making a process easier very often improves quality, speed, and cost, but that's not the focus. The focus is on the people making the product or providing the service, not the product/service itself. Putting humans at the center of kaizen is another example of respect for people. As Mark Hamel pointed out with regards to kaizen at Toyota,

Occasionally, the worker generates a great idea around quality or working process improvement. But, the primary focus for the worker is typically around the “humanization of work.“ In other words, it starts with making the work EASIER.

And this jibes with what Jim Womack wrote all the way back in 2006: that instead of focusing on waste, we should focus on unevenness (mura) and over-burden (muri).

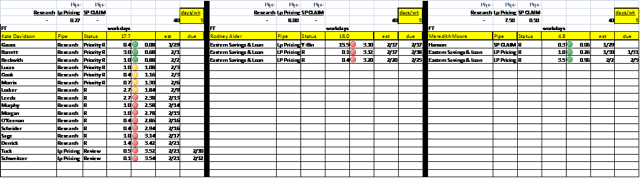

In most companies we still see the mura of trying to “make the numbers” at the end of reporting periods. (Which are themselves completely arbitrary batches of time.) This causes sales to write too many orders toward the end of the period and production mangers to go too fast in trying to fill them, leaving undone the routine tasks necessary to sustain long-term performance. This wave of orders -- causing equipment and employees to work too hard as the finish line approaches -- creates the “overburden” of muri. This in turn leads to downtime, mistakes, and backflows – the muda of waiting, correction, and conveyance. The inevitable result is that mura creates muri that undercuts previous efforts to eliminate muda.

Of course, if we make demand more even, and if we avoid overburdening people, we're essentially making the work easier.

Lean is often referred to as a total business system. As I continue to learn more about it, I see more and deeper linkages between areas that I never realized before. This is one example: how kaizen -- properly done -- is not just a way to remove waste or make more money. It's a profound expression of respect for people.

Download PDF

Download PDF