The soul-deadening excesses of corporate 5S tyrants continues to astonish me. While leading a workshop at a healthcare client last week, I learned that two of their internal lean champions—and I use that term VERY loosely—had become tin-pot 5S dictators. One of these so-called lean leaders forbade anyone to have more than a single personal photo on their desk. Another dim bulb insisted that everyone put blue tape outlines around their computer, phone, stapler, etc. These exercises in small-minded stupidity were all the more surprising because this is an organization that has been pursuing lean for several years now, has a lean leadership development program in place, and has been consistently working with an outside consultant.

I’ve written before about the absurdity and wrong-headedness of transferring 5S in a literal fashion from the factory to the office. Setting that equipment in “order” doesn’t accomplish anything, because—as far as I know—no one has ever lost their computer or their keyboard. Setting the information that office workers manage in order is a good idea, but not the computer itself. And as far as the one-personal-photo limit? That’s stupid. And cruel. And pointless.

5S is nothing more than a tool designed to solve specific problems, like abnormalities in a process that might otherwise be hidden, or wasted motion while looking for tools. But it’s a tool for a specific problem, not something to be slavishly and mindlessly applied because it shows up on page 34 of your Big Book of Lean. That makes as much sense as using a crescent wrench to hammer a nail. Or doing extended calculations in a table in Word.

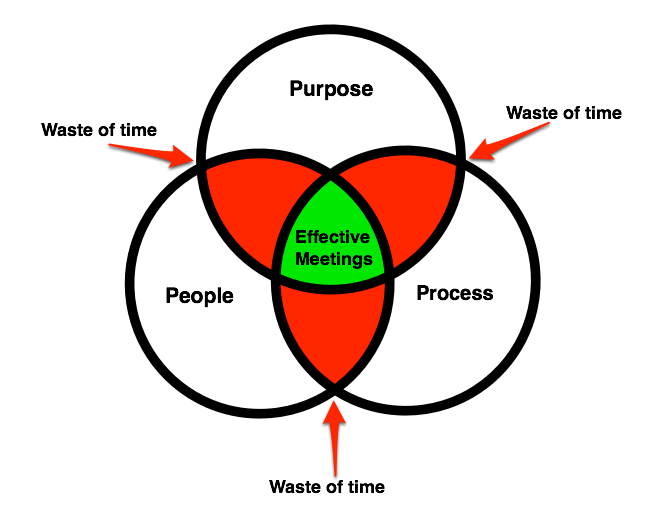

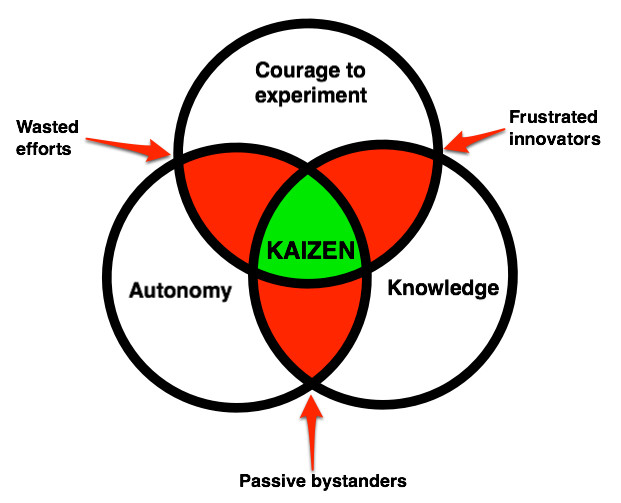

Whether you’re implementing an improvement program on your own, or you’re getting help from an outside consultant, you always need to start with this fundamental question: What problem am I trying to solve? The answer to that question will direct you to the appropriate tool (if it exists), or force you to invent your own.

Stop worshipping at the altar of Toyota. Instead, learn from Toyota. They invented tools to solve their specific problems at specific times. You need to do the same.

Commit to problem solving. Commit to learning. But don’t commit to 5S unless it's relevant for the problem you’re facing. Otherwise, all you’ll get is alienated workers who will leave you for an organization that allows them to have a picture of their wife AND their dog on their desk.