“Sorry about the mess. These are just the cases that came in the last couple of days. The big pile over there? That’s the research project that I’m supposed to be working on.” Megan sighed despairingly and waved her arm, indicating piles of unread slides stacked like ziggurats on every flat surface in her office. Megan is an experienced, talented, and very hard working pathologist at a major cancer hospital. Her days are spent with her face pressed up against the viewer of her microscope, examining tissue samples for evidence of malignant tumors. I was visiting her because she seemed to have lost her ability to read cases and turn them around rapidly for the referring physicians. Megan was caught in a bind: she was feeling pressure from her boss to work faster, but she was worried that reading the slides more quickly would increase the risk that she’d incorrectly diagnose a case.

Megan went on: “I used to be able to read more cases during regular business hours, but now I have to come in earlier and stay later just to keep up—and obviously, I’m not doing a particularly good job of that. Although to be fair, no one else in the department is either. We’re all feeling swamped.”

Frankly, I wasn’t sure I’d be able to help her. I’m neither a pathologist nor a doctor. (Which, since I’m Jewish, always made my parents very sad. They weren’t exactly cheering when I took a class in the Semiotics & Hermeneutics of the Mystery Story.) I know as much about interpreting tissue samples as I do about designing sub-atomic experiments for the Large Hadron Collider.

So I spent a couple of days watching Megan work. And what I saw reminded me of what Keith Poirier wrote on Jamie Flinchbaugh’s blog recently:

Lean is nothing more than the re-introduction of ‘common sense’ into our daily work lives.

I don’t know anything about interpreting biopsies. But it turns out I didn’t need to. What I saw was a doctor who seldom got more than eight uninterrupted minutes to analyze a slide. Practically every time she nestled up against her microscope, someone came into her office and interrupted her. Following each interruption, she’d turn back to the slide, and start re-reading it from the beginning to ensure that she didn’t miss anything. As a result, reading each case took three, four, five times as long as it needed to.

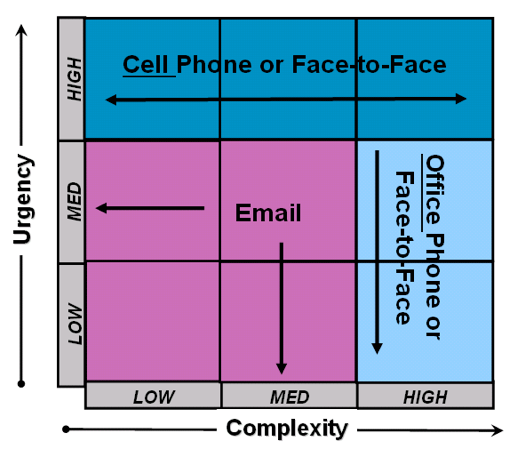

What’s worse, in the two days I watched her, none of the interruptions were urgent. In fact, the most common interruption was from technicians bringing her new slides to read. They’d walk in, say hello, tell her that they have new cases, and she’d tell them to just put them on the corner of her desk.

My solution? Put a cardboard box outside of her door with a sign telling the technicians to put all new cases inside it. Megan created a fixed schedule to pick up any cases every 90 minutes. Fancy, right? She cut interruptions by two-thirds, and cut the time it took her to process her cases by 40%.

We didn’t talk about takt time, pull systems, or kanbans. As Keith Poirier wrote, it’s just common sense. You’re not going to be able to do your work—whether that’s reading pathology slides, writing ad copy, calculating force vectors on bridges, or writing a patent application—quickly or efficiently if you’re always being interrupted. So we cut down the interruptions to help her do her work a bit better.

There’s still plenty of work to be done in that hospital’s pathology department. There’s waste all over the place. But by focusing on simple, small, and rapid improvements, we made a big difference in Megan’s performance—and her happiness.

I’ll slit my wrists if I have to read one more fawning article about Google’s eleven gourmet cafeterias, on-site car washes, and dry cleaning service. Or Pixar’s cereal bar (more than 20 varieties!), its lap pool, and the jungle-like cabanas and tree houses that serve as offices. Or Nike’s Olympic-size swimming pools and hair salon. Or Zappos’ life coaches.

Each of these firms was recently touted in an Amex OPEN Forum

I’ll slit my wrists if I have to read one more fawning article about Google’s eleven gourmet cafeterias, on-site car washes, and dry cleaning service. Or Pixar’s cereal bar (more than 20 varieties!), its lap pool, and the jungle-like cabanas and tree houses that serve as offices. Or Nike’s Olympic-size swimming pools and hair salon. Or Zappos’ life coaches.

Each of these firms was recently touted in an Amex OPEN Forum  Download PDF

Download PDF