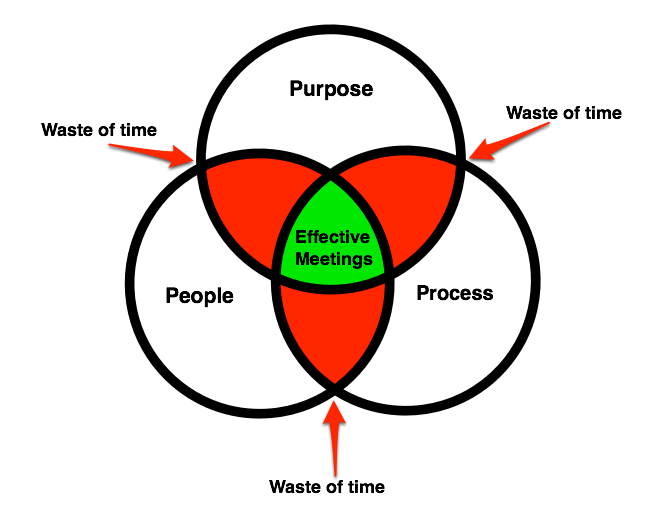

Three things in life are inevitable: death, taxes, and the inability of organizations to conduct meetings that aren’t a soul-sucking waste of time. You’d think it wouldn’t be that hard to have productive meetings—after all, Robert’s Rules of Order have been around since 1876, and legions of intelligent business consultants have written extensively on the topic. Yet survey employees in any organization about their meeting effectiveness, and you’ll be met with groans, eye rolls, and complaints about how low-value added they are. An easier approach to making meetings effective and productive is to follow the 3P Principle: ensure that you have the Purpose, People, and Process right.

Purpose: A clearly defined purpose for the meeting is essential. Purpose is not a topic or a subject; it’s a clear description of the desired outcome of the meeting. It’s a goal that everyone is driving towards. Purpose is often, but not always, a decision—whether or note to open a new office, or to delay the introduction of a new product. But purpose could be brainstorming (to generate 15 new brand names), or gathering information (to get the sales team’s perspective on the new bicycle frame material), or to ensure that everyone understands a strategic shift in direction (we’re abandoning the low-end of the market, and here’s why). Having a clear purpose focuses the discussion, keeps the meeting from wandering, and increases the likelihood that you’ll get there.

People: Are you sure you have the right people in the room? Meetings often deteriorate into irrelevance because the right people aren’t there. This isn’t news, of course, but it’s surprising how infrequently people take the time to figure out who should attend. Job responsibilities change without formal notification, and the person nominally handling a function may no longer be doing it. Moreover, even if you have the right person in the meeting, she might want a specialist from her group to join her so that she can offer better opinions. Therefore, in order to get the right people in the meeting, you need to talk to the participants in advance, explain the meeting’s purpose, and find out from them who the right people are for that purpose. Organizing and conducting a meeting is a team sport—you can’t do it alone.

Process: Is a meeting the right process to accomplish your purpose? Although meetings are a near-Pavlovian alternative to other forms of communication, it’s a good idea to first ask whether you actually need a meeting. Status updates don’t require people to be in the same room at the same time, and can be handled more effectively with asynchronous communication like email, memos, Sharepoint documents, internal Wikis, etc. Moreover, even when a meeting is the appropriate process for your goal, you need to examine the preparation for the meeting. For example, you can’t expect management to sign off on a major capital expense or a significant engineering change in a single meeting: you need to engage in the process of nemawashi (consensus-building) in advance to ensure that the meeting will be effective. Advance one-on-one conversations with key people provide the context for the request, enable you to understand potential objections, and ensure that you can present all the necessary information to enable participants to make a decision.

Time is the most valuable resource individuals have. Time that many people can spend together is even more precious and difficult to schedule. It’s incumbent upon us to use that resource as wisely as possible. If you can get the Purpose, People, and Process right for your meetings, you will make it more likely that the limited time you have together isn’t a waste of time.