If you’re trying to get fit, don’t try to lose weight. And if you’re a business trying to get “fit,” don’t try to cut costs.

Real fitness isn’t defined by overall weight, or by body fat percentage. Sure, if you’re 5’6” and weigh as much as a double-door Sub-Zero refrigerator, you should probably take a step back. Then again, if you’re a 5’10” fashion runway model tipping the scales at 102 pounds soaking wet, you’re probably not very fit either. The important point here, is that real fitness isn’t just about body mass index. It includes cardiovascular capacity, muscular strength, and flexibility. And if you’re an athlete—even a recreational one—you also need coordination, agility, speed, and quickness. You can’t gain those capabilities just by dieting.

There’s an organizational parallel here: a company can’t get “fit” simply by cutting costs. To be sure, you may be able to improve your income statement in the short term by laying off workers, closing offices, banning color copies, and no longer catering meetings. However, organizational fitness isn’t just about low expenses. It includes the ability to react quickly to market shifts, to create and deliver new products and services, and to continually improve process efficiency and effectiveness—all in the service of delivering greater value to customers. Cutting expenses as a way to organizational fitness is like cutting calories as a way to personal fitness. At its logical extreme, it results in corporate anorexia—a feeble organization filled with dispirited employees, unable to compete in the marketplace and serve customers.

Sunbeam Corporation is the poster child for this misguided approach. Sunbeam hired “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap (also known as "Rambo in Pinstripes") in 1996 to turn the company around. Dunlap, widely viewed as a turnaround expert, was legendary for his ruthless approach to financial improvement, which typically involved firing a large portion of the workforce. True to form, within a year, he laid off half the company’s staff (6,000 people) and eliminated 90% of the company’s products. This lowered expenses by $225 million per year and nearly quadrupled the stock price in less than two years. But cutting costs has its downside. He moves made the company less capable of reacting to customer needs -- and by 2001, the company was bankrupt.

There’s another parallel between dieting and simple expense cutting: neither work in the long term. It’s common knowledge that the vast majority of people who lose weight on a diet regain it within a year or so. Organizations that just cut expenses tend not to maintain their new weight either. There’s no concomitant reduction in work after layoffs—it simply gets shifted around. Employees take on the additional responsibilities of a colleague or a boss. They work longer and harder, but because the underlying processes aren’t functioning any better, and because these companies haven’t focused on improving how they operate, work doesn’t get done faster, better, or more easily. Eventually, after the financial crisis passes, the organization eases travel restrictions, permits color copying, and starts catering meetings again. Gradually, the company hires people to refill the roles that were eliminated earlier. The weight comes back on, and the organization is just a market downturn away from another round of layoffs and cost cutting.

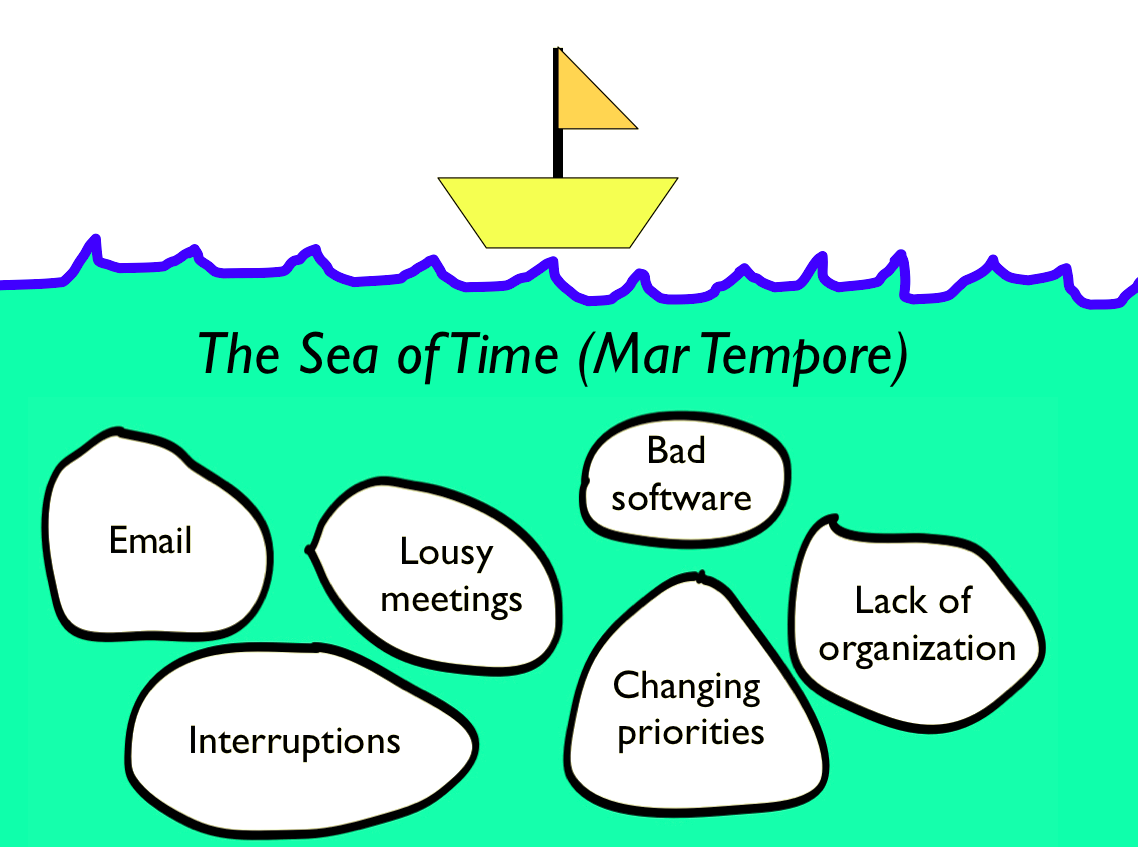

The alternative is for organizations to focus on building fitness, not on reducing costs. In this context, fitness means becoming faster, more agile, and better able to take advantages of new opportunities and serve customers better. It means examining the processes by which the organization operates. It means focusing on the means by which work is done, not the (financial) ends. A corporate “fitness program” develops employees’ capacity to solve problems and improve performance, with the long-term goal of increasing the value provided to customers. And with greater customer value comes improved financial performance. In fact, cost reduction is an inevitable outcome of the pursuit of fitness—but cost reduction is not the primary objective.

Wild Things Gear makes technical outdoor apparel that consumers can customize for their own needs. The company is a perfect example of how rethinking processes can make an organization more agile and better able to adjust to market shifts. CEO Ed Schmults believes that customization is especially important for technical clothing, because it allows customers to create the functionality that’s important to them.

Product customization is nearly impossible if you manufacture in Asia (like virtually all outdoor companies). Asian factories are built for mass production: long production runs of hundreds or thousands of garments with minimal variation. It’s also tough to get products to consumers quickly if they’re produced halfway around the world—ocean shipping, customs clearance, and logistics (ocean port to warehouse to consumer) adds three to four weeks of transit time. Airfreight is much faster, of course, but it’s cost prohibitive for the company, since most consumers aren’t willing to pay for that service.

Schmults realized that to deliver the increased value that comes with a customized product, he’d have to develop the ability to make clothing in the United States. He’d have to get faster, more productive, and more skilled in apparel manufacturing—a tough job, given that the domestic apparel industry has been eviscerated over the past 20 years as companies have closed their factories and outsourced their work to Asia. However, using lean manufacturing techniques such as cellular production, one-piece flow, kitting of components, etc.—along with extensive training—Schmults was successful in making technical outdoor gear in the US. Now, with a website that allows customers to configure their products online, domestic production, and the elimination of retailers for distribution, consumers can go from designing their own jacket to delivery at their house in only 14 days.

So, more value to the consumer—but what about the company? Moving away from traditional overseas mass production has meant faster production, less finished goods inventory, and lower working capital requirements. Quality is higher, and overall costs are lower. Indeed, even as sales are growing steadily, the company’s return rate is only 6.8%, whereas most fashion brands have return rates as high as 40%—and that difference goes right to the company’s bottom line.

That’s what real corporate fitness looks like. Not layoffs. Agility.

Quisque iaculis facilisis lacinia. Mauris euismod pellentesque tellus sit amet mollis.